Introduction

(There is a summary of this page below, here)

This page will look at economic contributions made in the run up to what has come to be known as ‘Political Economy’, which will be considered on following pages.

Here it will again be useful to follow the lectures of Lionel Robbins (Robbins 1998), delivered at the London School of economics during 1979-1981, when the lecturer was in his eighties. All unattributed page references will be to that publication.

At the same time, as more modern thought is approached many more reference sources become available, some of which will be included alongside Robbins where they throw more light on matters.

Robbins made a distinction between ‘anticipations’ in economic thought and modern economics proper, based on the treatment of the economy as a system.

This distinction is of course a crucial one. Describing economists who think in this way, Robbins says they approach the study of economics as “… a system of relationships … [where] … you could try out hypotheses which would explain variations in the relationships of the system as a whole … [relationships] not only connected at one point in time, but being connected through time” (P 99).

It is worth noting here though, that not only is it important to have a general systems view of the economy, it is also important to accurately specify the component parts of that system and the relationships between them.

It seems that many of the major differences in economic theory derive from different views of the nature of these system components and of the ways in which they interact.

In this section the emergence of systems thinking, and other advances, is traced though the contributions of French writers Richard Cantillon and the later Physiocrats; followed by the Scottish writer David Hume.

Richard Cantillon

1680s – 1734

Robbins begins with a discussion of Richard Cantillon, whom he clearly holds in high regard. Cantillon, born in Ireland, moved to Paris very early in his life. There he became a banker, and was eventually involved in an infamous financial collapse – the Mississippi scheme of John Law. Cantillon shrewdly got out of the enterprise before the collapse, after having made a large fortune.

He subsequently began to collect economic data, to read existing economic material and to write his own thoughts on the subject. Then, in 1734, he was murdered by an employee, who set his house on fire, destroying much of his work.

Various economists have since pieced together his writing, and several editions have been published over the years, accumulating as much of his work as possible. This is known as his “Essay on the Nature of Commerce”, first published in 1755.

One aspect of his work has never been recovered however. This was his Supplement, a collection of empirical data to which he refers to illustrate and support his ideas.

Robbins describes the ‘Essay’ as a systematic, abstract treatise on the economic system, informed by a close acquaintance with the workings of commerce, finance and trade of the time. He sees the work as an ‘extraordinary’ document comparable to that of Adam Smith and other pivotal contributors (P80).

This is how Robbins summarises Cantillon. The ‘Essay’ is comprised of three parts, of which Robbins examines parts 1 and 2 in much more detail than the last part:-

Part 1 is a general analysis of the working of the economy

Part 2 is a more detailed discussion of monetary and interest theory

Part 3 is an ‘incredibly well informed’ discussion of commerce and banking

Part 1

In Chapter 1, Cantillon lays out these precepts; “The land is the Source or Matter from whence all Wealth is produced. The Labour of man is the Form which produces it: and Wealth is itself nothing but the Maintenance, Conveniences and Superfluities of Life” (Quoted by Robbins P 81).

Chapter 2 discusses human societies in general and the function of property in any complicated society. He then discusses the different kinds of human settlements in such a society, and the relationships between them; thus,

Villages – where it is convenient for some to live together, near the place of their agricultural labour.

Market Towns – which are bigger can support markets that supply all of peoples requirements, in a way not possible in villages.

Cities – where some of the rich landlords will live, having more complex requirements and benefitting from the developed commerce of the city.

Capital Cities – which provide the seat of Government and the residence of the monarch.

It is as though he is starting to specify the components in the economic system as he sees it.

Later chapters look at economic relationships in more detail, describing the consequences of the different training that is needed for different occupations.

Cantillon writes “The labour of the Husbandman is of less value than that of the Handicraftsman” (Quoted P82).

This is because an agricultural labourer’s son can help with the work of his father from the age of 7 upwards with no formal training. A man who puts his son to learn a trade however is faced with supporting the boy through years of apprenticeship, feeding and clothing him, and could not do so if the eventual craftsman did not earn a higher wage than the agricultural labourer. For society also, in order to maintain a flow of needed craftspeople, there needs to be a pay advantage involved.

Moreover, some trades entail more training than others and hence draw more pay; therefore, says Cantillon, the different prices paid for different types of daily work are easily understandable.

Then he says, on a larger scale, the number of labourers and craftsmen and other workers in a State will be proportional to the demand for them. In a village where demand falls there will be a wastage and migration away when people have to search for work elsewhere. When, on the other hand, demand rises in a village that situation will reverse, and there will be a migration in of workers.

This way of thinking says Robbins, foresees the idea of an equilibrium process working in the economy – an important concept in later economics – where the number and different kinds of labour respond to fluctuations in demand.

In Chapter 10, Cantillon “‘is confronted with the theory of price” (P 82), and introduces what he calls the ‘intrinsic value of a thing’, which is the price around which the market price will oscillate. Robbins quotes Cantillon as saying “… the Price or intrinsic value of a thing (in general) is the measure of the quantity of Land and Labour entering into its production” (P82).

Cantillon next takes on William Petty’s issue of the par between the two sources of value, Land and Labour. He asks the question says Robbins, “How do you assimilate quantities of land and quantities of labour in deciding what is the intrinsic value or price of this thing or that?” (P 82). Note that value and price seem to be used interchangeably here.

Cantillon proposes to solve this problem by deciding on the area of land, or rather the area of two quantities of land. The first is the area necessary to produce the commodity in question: the second is the area needed to produce the subsistence of the workers needed to produce the commodity itself.

He accepts this is only an approximate method as, for example, the necessary subsistence of the workers will vary in different circumstances. But for Robbins it is the best attempt ever made to solve Petty’s question; however he adds “it won’t help you much in deciding the normal value of prices in advanced communities” (P83).

Note that the distinction between value and price is further blurred here, with Robbins’ phrase ‘value of prices’.

Cantillon, in the remaining Chapters of Part 1, covers a number of other factors.

- He writes that everyone in a state subsists or are enriched at the expense of landowners. Robbins feels this view is akin to, but less doctrinaire than, the Physiocratic view that agricultural and extractive labour is the only productive labour, other types being seen as unproductive.

- In discussing the organisation of production and accumulation of goods, he identifies 3 economic classes in society:-

- The landed aristocracy

- Entrepreneurs, who take on economic risk by hiring

- Those who work for fixed wages, agreed beforehand

This is Robbins first known use of the word entrepreneur in economics.

- He next identifies 2 groups in society; those who are hired at fixed prices beforehand, and those who are unhired – effectively speculating on future markets. Again for Robbins, no more useful demarcation in this respect has ever been made.

- Turning to demand he then argues that the ‘Fancies and Fashions’ of the Landowners and the ‘Prince’ determine the uses to which the land is put, and cause fluctuations in market prices across the economy.

- The population level too, he says, depends on the fancies of living of landowners. He refers to the lost supplement here, saying that he has estimated the amount of land needed to support the lifestyle of people of different types.

So, many of the peasants in France living on basic food and with plain clothing can live on the produce of an acre and a half; the ‘ladies of Paris’ by contrast, adorned with Brussels lace, would need 16,000 acres to support them.

Turning to William Petty’s extrapolations of population levels from a few districts, he instead links population to living standards and land in a famous statement:-

“Men multiply like Mice in a barn if they have unlimited means of subsistence, and the English in the colonies will become more numerous in proportion in three generations than they would be in thirty in England, because in the Colonies they find for cultivation new tracts of land from which they drive the Savages.”

Quoted by Robbins (P 84) where he substitiues the word ‘savages’ with ‘inhabitants’ to avoid giving offence to modern audiences.

He then states the view that ‘The more labour there is in the State, the more natyrally rich the state is esteemed’; of this Robbins says Cantillon takes the common view, implying his own disagreement.

Cantillon’s last chapter of Part 1, on money, is passed over by Robbins as a standard Aristotelian view, before Part 2 Chapter 2 follows, dealing with ‘the formation of market prices’.

Robbins feels this Chapter is extremely important, describing a ‘most original contribution’ where he describes for the first time known to Robbins, “the mechanism whereby the varying disposition to demand and the varying disposition to supply eventually produce market prices” (P 86. Italic present in the original). He then quotes a passage he likens to an ‘early Austrian Model of the market process’.

Summarised here Cantillon describes a scene illustrating the mechanism of the supply and demand process.

In Paris, four Masters tell their maitres d’hotels (buyers A, B, C and D) to buy a quantity of green peas at the market, at the following prices;

A – 10 quarts of peas at 60 livres

B – 10 quarts at 50 livres

C – 10 quarts at 40 livres

D – 10 quarts at 20 livres

He then imagines two situations; in the first case the market has only 20 quarts of peas available for sale: in the second there are 400 quarts for sale.

In the first situation, 20 quarts available, the market traders, seeing many buyers for their few peas keep their prices up. Buyer A will be served first with 10 quarts for 60 livres; then seeing no one else will pay that amount, the price will be dropped and buyer B will be served with the remaining 10 quarts for 50 livres. Buyers C and D go away empty handed.

In the second situation, 400 quarts available, the traders seeing only a few buyers for their large stock of peas, will lower their prices almost to the intrinsic value. This time all 4 buyers A, B, C and D will get their 10 quarts for much less than they expected, and in addition many other buyers – seeing a bargain – will buy peas also.

Cantillon subsequently adds refinements to his view of market price formation. For example:-

- If the price in a particular market is very low, then some sellers may think of going elsewhere to sell in a different market.

- He thinks that prices in general are likely to be lower in areas far distant from market towns and cities.

- Similarly, those manufactures that don’t involve heavy transport costs could be more profitably run in such distant places, with lower running costs than in places close to cities.

Circulation of Money

Cantillon then turns his attention towards money. He starts by saying that farmers must make three ‘rents’;

- One to the proprietor of the land, supposedly equal to 1/3rd of his annual produce

- Another 1/3rd to cover his own maintenance and that of the men and horses he uses to work on his farm

- And a 3rd he keeps as profit

This discussion then leads into a consideration of the circulation of money, he considers;

- The demand for money for the purpose of guarding against risk

- The habits of landowners, and the people they buy from

- Manufacturers, and how they spend their money

- Banks, and goldsmiths (who were changing themselves into banks at that time), arguing that banks help to make the circulation of money more rapid

This is followed by a discussion of Locke’s view that market prices are regulated by the quantity of money in circulation, relative to the quantity of produce available. Cantillon says that Locke did not explore the mechanisms involved in this process, the ways and proportions by which circulating money raises prices.

Then, says Robbins, in a ‘thrillingly original’ discussion Cantillon examines minutely the ways in which money in circulation may be increased, for example via the flow of precious metals from mining or from a favourable balance of payments. Then he considers the ways in which money spreads within a community;

- Thus rises in price will depend upon whose hands the money gets first

- If it goes to those with little demand for money, they pass it on quickly leading to price rises

- If it goes to those who hoard money, prices are not immediately affected, but will rise eventually as hoards sooner or later get spent

By this he concludes that doubling the money in circulation does not necessarily double prices, just as,

“A river which runs and winds about in its bed will not flow with double the speed when the water is doubled” (Quoted by Robbins P88)

Cantillon then concludes with section dealing with interest rates, and banking; both dealt with briefly by Robbins.

On interest rates he attacks the view that interest rates are simply and instantly affected by the quantity of money. He notes the complexity of the money market, says that the main demand for loans comes from those involved in manufacturing and the like. He then favours a ‘more or less’ loanable funds account of interest, where rates are determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds.

Finally he considers trade, foreign exchange and banking, concluding with an emphasis that banking and bank credit economises the demand for hard money.

Summary of Cantillon

Cantillon produced what Robbins felt was an extraordinary, systematic and comprehensive analysis of the economy as a system, comparable to the work of Adam Smith. His contribution covered:-

- Precepts defining land and labour as the sources of wealth

- Descriptions of the components of the economic system and an analysis of the causes of wage differentials, and the hint of a theory on equilibrium processes

- The argument that market prices oscillate around what he calls the ‘intrinsic value’ of items, which he sees as the measure of the quantity of Land and Labour entering into their production

- The delineation of 3 economic classes in society;

- Landed Aristocracy

- Entrepreneurs

- Wage earning workers

- The introduction, for the first time, of the term ‘entrepreneur’ into economics

- The development of William Petty’s ‘par’ of Land and Labour, and the calculation of the land equivalents required to support the lifestyles of those in differing social positions

- The mechanism of the processes determining market prices

- The elaboration of the quantity theory of money to stress the importance of the varied circulation paths of money in the influence on price levels

- Contributions on Interest rates, foreign exchange and banking.

Physiocracy

Robbins continues his account of French economics when he next turns to the proponents of a distinctive school of thought, and who became known as the Physiocrats. He begins by outlining the economic background in France in the mid 18th century.

During the long reign of Louis XIV (‘The Sun King’), who ruled from 1661 until his death in 1715, France was involved in not a few wars, while an extravagant & opulent aristocratic lifestyle contrasted with the ‘tremendous and agonising’ poverty of the peasant population.

Economically France was run under a variant of Mercantilism under the direction of Colbert, the minister of finance. This system, Colbertism, was characterised by the objective of a favourable balance of trade, design of the tax system to improve national wealth, increasing of the Royal revenues and improvements in trade and industry.

Robbins describes the French population, in the early part of the 18th century, impoverished by war and by an iniquitous tax system, where Colbertism favoured manufacturing at the expense of agriculture in which most people were occupied. In this situation public discussion of economic matters were discouraged.

A further matter added to the disfavour with economics, the notorious Mississippi Bubble. Here, in 1719 the Scottish economist and gambler John Law influenced the French regent into jointly launching the ill fated Mississippi Scheme. Law wanted money to be issued on the value of land, an almost inevitably inflationary scheme.

The project soon collapsed, a much bigger disaster than the South Sea Bubble, hitting investors from all classes and ruining the already weak French economy, such that it took years to recover.

As a result of these factors there was very little written in France on economic matters until the 1750s and 60s, when there was a “terrific outburst of economic speculation” (P 92) from the Physiocrats (Cantillon wrote in the early 1700’s but was not published until 1755).

Robbins, who saw the Physiocrats as much less impressive than Adam Smith and David Hume, identifies Quesnay (1694 – 1774) and Turgot (1727 – 1781) as the leading intellectuals associated with the movement. Quesnay was a physician who came to prominence after publishing works on the circulation of blood in the human body. He achieved eminence though after treating a high ranking Court lady for an epileptic fit at a fashionable Versailles party. Following this he was recommended to Madame Pompadour under whose protection he subsequently fell.

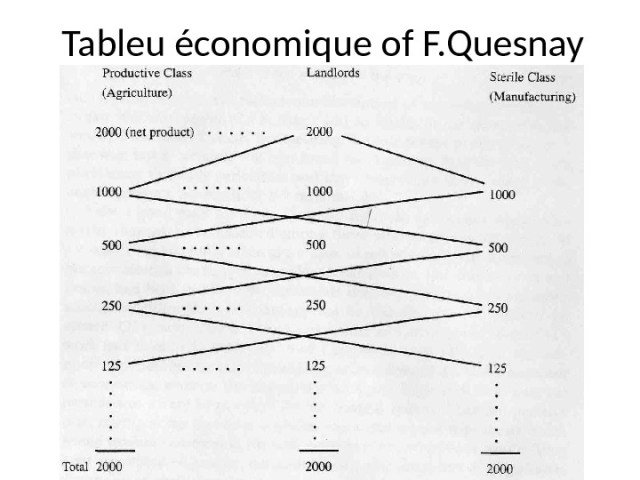

By this time Quesnay had become something of a landowner, and in the context of Colbertism disadvantaging agriculture, he turned his attention to farming policy and reform, and thence to general economic analysis. Then in 1758 he published the famous ‘Tableau Economique’ dealing with the circulation, not of blood in the body, but of money in society – seen as no accident by Robbins.

Quesnay’s work avoided the isolation that befell Cantillon’s when he was taken up by the influential Marquis de Mirabeau (1715 – 1789). Mirabeau, whose son Honore later became a famous figure in the French Revolution, already had an interest in economics and was well known after writing a popular book – ‘The Friend of Man’ – that drew heavily on Cantillon.

Mirabeau introduced Quesnay’s work to a group of influential people who went on to form a veritable school, with its own journal, books and meetings. The school became fashionable with the Royalty of Europe, and there was a general optimistic feeling that this was a new branch of knowledge that would be the basis of a just and happy society.

Mirabeau rather flamboyantly claimed that Quesnay’s invention of the Tableau Economique was comparable with the invention of writing and of money.

The Substance of Physiocracy

Robbins indentifies 3 underlying currents of Physiocracy.

- They were heavily pro-agriculture and against the Colbertian promotion of manufacture.

- Their general attitude to Government was ‘laissez faire’ – more so than Hume and Adam Smith whose position Robbins felt was more complicated.

- They adhered to a view that policy should be shaped according to ‘natural law’ – again at variance with Hume and Smith who held to an essentially ‘utilitarian’ position.

While the term ‘laissez faire’ is familiar enough – the view that the economy and markets work best when government intervention, such as regulation and subsidies, is kept to a minimum, the ‘natural law’/’utilitarian’ contrast merits a brief elaboration.

Broadly speaking the idea of ‘natural law’ holds that some Deity, or simply Nature itself, has lain down providential rules, possibilities or constraints for the maintenance of a harmonious universe, and which should govern human social and economic actions. Alternatively ‘utilitarian’ ideas hold that human actions should be judged according to their utility – their benefits to people and society.

Economic Ideas

From these 3 undercurrents Robbins identifies the following economic ideas and analyses:-

- The population was classified into three groups, based on the idea that only agriculture (and later mining, quarrying etc) were productive:-

Landowners – rightful recipients of the overall net product, based on their original efforts to make the land fertile, and the class who should bear all taxation.

Agricultural labourers – those who worked productively on the land, but receiving wages that tended towards subsistence.

Manufacturing workers – an unproductive ‘sterile’ class whose labours were useful but only amounted to ‘moving about’ the wealth that had been produced from the land.

- Based on this classification they identified a theory of economic distribution:-

The work of the productive agricultural workers produced an annual flow of wealth resulting in a ‘net product’ or surplus, which became the property of the landowning class.

The landowners then made advances from the flow to both the productive agricultural workers and the unproductive manufacturing workers for agricultural or manufactured products respectively. The flow was then further divided amongst the classes as manufacturing workers needed agricultural produce, and vice versa.

It was fundamental to the physiocrats that payments made to the sterile class of manufacturers should not encroach on those made to the productive agricultural class, otherwise the net product would decline, and overall social wellbeing with it.

- The Tableau Economique became a means to model different economic situations, to theorise about economic equilibrium, and to propose optimal economic policy decisions.

The Tableau Economique

The physiocrats produced various more complex variants of the Tableau, but the following figure represents the basic ideas in a simple manner (Meek R L 1962, P 20 – 22 and 276 – 78).

The tableau represents a period of economic activity, say one year. The columns represent the three classes, which are all simplified in the table to aid illustration of the main flow of wealth. Thus the Landlord class will include the King and the Clergy, while both the agricultural and manufacturing class will be internally differentiated between workers, employers and entrepreneurs etc.

At the start of the year the Landlord class have received 2000 units of currency, say livres, in rent, paid to them by the agricultural class, and equal to the net product. The agricultural class hold part of their previous year’s produce, as do the manufacturing class.

In the current year the landlords start by buying 1000 livres worth of produce from both the agricultural and manufacturing class. Subsequently there are repeated exchanges of agricultural and manufacturing produce as the other two classes buy from one another.

This consumption stimulates more agricultural and manufacturing production throughout the year; and if the resulting aggregate receipts accruing to the 2 classes just cover their costs of production, and enables the agricultural class to pay rent to the landlord class, then the level of economic activity in the following year will stay as it is in the current year (Ibid P 21).

The Table and description above describe the main ideas of physiocracy – productive agricultural workers, proprietors who receive the net product and the sterile manufacturing class.

However, the physiocrats went much further than this static view, where the net product is maintained at the same level year after year, period after period. Quesnay and Mirabeau produced versions of the table to show situations that would produce declining states of the economy, or of advancing states – economic growth. They also deduced from the table that all taxes should fall upon the net product of the proprietor class, in order not to hamper the productive or useful labour of the other classes.

Robbins summarises his views of the physiocrats thus;

- The main physiocratic idea – the view that only the produce of agriculture and of mineral extraction produced an economic surplus, and that manufacture produces no new ‘stuff’, it only covered its cost of production by ‘moving around’ existing stuff – was misleading.

- At the same time both Adam Smith and Marx adopted a similar distinction between productive and productive labour – but in their case productive labour was that which contributed to the accumulation of capital, and unproductive labour that which left nothing behind. Smith’s examples of unproductive labour was that performed by Royalty and by ballet dancers. That distinction was seen by Robbins as more meaningful than that of the Physiocrats, but he makes clear that he does not subscribe to it himself.

- Strongly in their favour was the phyiocratic view of the economy as a system as a whole, putting them amongst the originators of economics as the study of a system of relationships. They also saw the system as something that could be modelled giving the ability to try out explanatory hypotheses, even including quantitative aspects.

- Moreover, they saw the system as working through time, as a process in time; changing the focus of study from wealth to the flow of wealth.

- What of the Tableau Economique itself, seen by Mirabeau as comparable to the invention of writing? Adam Smith saw it as based on the mistake of seeing classes as existing in fact, rather than just as analytic categories.

Robbins then assesses the table against claims it might be a pre-cursor of a number of modern perspectives (all of which will be examined elsewhere in the blog). They were in turn; the marginalism of Walras, the economics of Keynes, post-Keynesianism and finally, underconsumption theory.

He finds it lacking on all sides; Walras, because it lacks any tendency towards equilibrium; Keynes because there is no ‘multiplier’; post-Keynesianism because there is no ‘dynamic analysis’; and underconsumption theory because physiocratic views of hoarding and overinvestment lack specificity.

- The most generous interpretation for Robbins is that the table could be adapted to a simple ‘Leontief’ approach, an input/output system such as is used to model interlocking branches of a national economy.

In concluding this look at Physiocracy, Dobb (1973 P 41) adds to Robbins list, by pointing out that their unique contribution was to put the source and explanation of the ‘produit net’, or surplus as the pivot of their system.

The source of surplus in the economy is of course central to this blog.

Turgot

Following his discussion of the Physiocrats, Robbins spends a short time on the work of a friend and associate of theirs, Turgot (1727-1781), a government bureaucrat who found time to write on economics. Turgot, and his most substantial work, ‘Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth’ (1770), get far more approval from Robbins than the Physiocrats themselves.

Turgot’s ‘Reflections’ clearly puts forward physiocratic views in its early parts, but later expresses what Robbins calls “ … a far more modern outlook …” – by which he clearly means the marginalist outlook on the economy.

The following quotes show that for Turgot, the distinction between agriculture and manufacture regarding productivity cannot be sustained; and that profit – surplus – can result from capitalist production. Thus Turgot says,

“There is another way of being wealthy without working and without possessing land …” Turgot 1770 P134 – 5) quoted by Robbins P?

Then, after a diversion into monetary theory, he talks of money in the economic system as a facilitator of the separation of the different labours between people in society, and,

“… the reserve of annual produce, accumulated to form capitals … (and) … Moveable wealth (as) an indispensible prerequisite for all kinds of remunerative work.”

He then talks of the necessity of advances in agriculture and in manufacture, and on the nature of these advances,

“he who sets men to work, provided the materials himself and paid from day to day the wages of the Workman.”

After discussing subdivisions within the industrial and stipendiary (rather than sterile) classes – he talks of entrepreneurs and workmen,

“ … they buy in order to resell; and that their traffic depends upon advances which have to be returned with a profit, in order to be newly invested in the enterprise …”.

(All quotes from Turgot 1770, in Robbins P 101 – 102).

Turgot, then, goes further than the Physiocrats in identifying the possible sources of surplus. Whilst the Physiocrats saw it resulting from nature, through agriculture, Turgot saw it resulting from an essentially capitalist process in agriculture or manufacture. Of course he did not pin down the precise source of that surplus within the capitalist production process, and theories of that source were developed in later economic theory, to be discussed elsewhere in the blog.

To conclude this section, given Robbins extremely brief and time strapped treatment, it is convenient to turn to an overall summary of Turgot’s contributions from the Econlib website. Econlib – ‘the Online Library of Liberty’ – is provided by Liberty Fund, Inc., a non profit foundation promulgating libertarian views. This summary is probably likely to largely concur with Robbins own views.

Econlib sees Turgot as ‘the French Adam Smith’, his ‘Reflections’ predating Smiths Wealth of Nations by 10 years and anticipating many of the latter’s insights. Thus Turgot,

- Argues against government intervention in the economy

- Recognised the function of the division of labour

- Investigated the determination of prices

- Analyzed the origins of economic growth

Regarding the latter, Econlib sees Turgot’s most important contribution as the recognition that capital is necessary for economic growth; and that capital can only be accumulated if overall consumption is less than production.

He also agreed with Quesnay’s idea of the circular flow of saving and investment, where today’s savings are tomorrow’s investment.

In addition he noted that interest is determined by the supply and demand for capital; and that in a competitive free market the rates of returns for all investments will tend towards equality.

Regarding commodities Turgot distinguished between ‘market price’ – determined by supply and demand – and ‘natural price’ – the price it would tend to in competitive conditions with free movement of resources. Thus an increase in demand for an item would likely increase its price, but if resources were free to enter into the industry that produced it, supply would increase and bring the price back down to its ‘natural’ level.

Finally, Econlib argue that in agriculture Turgot predated marginalism by 100 years by recognising the Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns (this proposal will be dealt with in another part of the blog). Thus he argued that ‘each increase in an input would be less and less productive.’

Following this look at French 18th Century economic contributions attention now moves back to British or even Scottish works that were pre-cursors of Adam Smith.

Locke and Hume on Property, Hume on Money, Trade and Interest

Locke on Property

John Locke (1632 – 1704), was an English philosopher seen as a hugely influential Enlightenment thinker, and has been called the father of Classical Liberalism. Better known for social contract theory, he also made economic contributions.

Robbins (P 105) draws attention to Locke’s second essay on Civil Government (1690) which he sees as “one of the great seminal works of political philosophy and political science”’

(He also sees it as a “the great apologia for the principles of the great and glorious and bloodless revolution of 1688”. This was the overthrow of James 11 of England by a union of English Parliamentarians and William of Orange, who became William 111 of England; seen as the event that permanently ended any chance of Catholicism being re-established in England).

In that work Locke first develops what appears to be a labour theory of property, where all are entitled to own the fruits of their labour. He then goes on, however, to justify the accumulation by some of property derived from the labour of others.

He starts by asking, that as God gave the earth to all mankind, how can it be justifiable for individuals to own little bits of it? He gives examples of hunters killing game that roams freely on common land, or people gathering nuts, and says that the hunters and the gatherers are surely entitled to keep their prey and their gatherings. They should not keep so much that the produce decays and goes bad however.

He then considers the case of land (all this against the background of the recently colonised continent of North America) and says that those who clear areas of land of trees are similarly entitled to keep that land.

This labour theory of property is then compounded by Locke when he says that 90% of most commodities in advanced societies result from the labour that has been expended on raw materials.

Perversely, for Robbins, Locke then considers gold and silver, which do not deteriorate, and which by social contract people have agreed to use as money. As this is so, says Locke, there can be no objection to people accumulating money and using it to buy land, and presumably other property originally produced by the labour of others.

Robbins is not convinced that Locke’s logic is consistent here, but notes that this is an “apologia which was bandied about in the political discussions of the eighteenth century” (P 106).

The “Essays” of David Hume are considered next, covering property, money, interest and the balance of trade. According to Robbins these “… set the tone, and in some ways are superior to most propositions of Adam Smith and most of the transitory comments of nineteenth-century classical economists …” (P 110).

David Hume (1711 – 1776) was a highly influential Scottish philosopher and empiricist, clearly held in very high regard by Robbins. He argued against the existence of innate ideas, positing that all human knowledge is ultimately founded solely in experience.

Hume on Property

Hume deals with property in his essay “Concerning the Principles of Morals” (1751), where he writes about ‘justice’ – where he refers to justice in relation to the rules and laws of property, rather than to matters of criminality.

He argues that property justice is as it is because it is considered to be socially useful. He then defends his argument by means of a series of hypothetical models of society.

In model one, he imagines a society of ultimate abundance, where all scarcity has been left behind and where it is taken for granted that every imaginable human want or need, physical or emotional, is met without the need to work or to give anything in return. In such a society he says our own system of property justice would never have been developed because all would have more than enough of everything, to make it irrelevant.

He suggests access to air and water as examples of substances freely available, in most parts of the world, where no one would be offended ‘or commit injustice’ by the most lavish use.

In model two he describes a society materially much the same as our own, but where human friendship and generosity are developed to such heights that everyone in all situations puts other people’s rights and comforts before their own.

This society too would have no need for our system of property justice, because any possible need or want that occurred to anyone would already have been anticipated and met by someone else. Why hold someone to a contract when I know that they will always put my interests before their own.

He suggests some families as situations that might approximate to this model.

Finally, he posits a third model, a society much as our own that befalls such a calamitous situation of universal shortage that mass starvation threatens and misery for all is guaranteed. In such a situation, says Hume, it is clear that the usual rules of property would be suspended and would be replaced by measures of necessity and societal preservation.

Contemporary examples, close to even this situation, exist he says where local shortages impel the public to open granaries without consent, confident that they would be treated with lenience in any repercussions involving the magistracy.

The lesson from these imagined situations, says Hume, is that societal rules of property, equity and contract depend on the prevailing conditions in a society. Extremes of abundance, scarcity, generosity, or its opposite rapacious selfishness, make our own rules of ‘justice’ useless and irrelevant.

Robbins then quotes this passage, as encapsulating Hume’s argument,

“The common situation of society is a medium amidst all those extremes. We are naturally partial to ourselves, and to our friends; but we are capable of learning the advantage resulting from a more equitable conduct. Few enjoyments are given us from the open and liberal hand of nature; but by art, labour, and industry, we can extract them in great abundance. Hence the ideas of property become necessary in all civil society: Hence justice derives its usefulness to the public: And Hence alone arise its merit and moral obligation” (Quoted by Robbins P 109).

Hume then expresses the familiar view, going back as far as Aristotle, that property is best looked after if the person or small group owning it have a direct interest in its preservation, than when that is not the case and when there may indeed be a more wasteful use of it.

He adds to his views on property by opposing those who argued at the time that property laws derived from some sort of natural instinct or natural law, rather than from their public usefulness.

“Look round at society” he says, “Look at the ways in which the law of property differs in different societies” (Ibid).

Hume then says, in effect, that a hundred different instincts would be needed to explain the hundred different variations in property law found in different societies.

He concludes by lingering on “… the fact that the law relating to property is subject to change by evolution, by consideration of changes in the conception of public utility …” (Robbins P 109).

Hume on Money

This statement opens Hume’s contribution,

“Money is not, properly speaking, one of the subjects of commerce, but only the instrument which men have agreed upon to facilitate the exchange of one commodity for another” (P 110).

The quantity of money, he says, if considering a single kingdom by itself, is of no consequence “… since the prices of commodities are always proportioned to the plenty of money” (P 110).

He notes however, despite the above, that since the influx of gold and silver from America,

“… industry has increased in all the nations of Europe … and this may be justly ascribed … to the encrease of gold and silver … [and that] … we find that in every kingdom into which money begins to flow in greater abundance than formerly, every industry gains life” and merchants, manufactures and farmers all “… raise their gains”.

To account for this apparent anomaly Hume goes on to say that although high prices result from increases in gold and silver in the economy, that result does not occur immediately. He argues that in the process of the extra money being dispersed across society industry is stimulated. Manufacturers and merchants can employ more people; workers receive higher wages, can eat and drink better and spend more at market; farmers and gardeners sell more and can afford better clothes from tradesmen … and thus it goes on.

In the intermediate situation between the influx of gold and silver and the eventual rise in prices, industry and enterprise is stimulated throughout society.

On this basis he recommends that, “The good policy of the magistrate consists only in keeping [the quantity of money] still encreasing … by that means to keep alive a spirit of industry” (Quoted by Robbins P 112).

Hume adds that the opposite situation, when the quantity of money falls, produces a period when people are ‘weaker and more miserable’.

To summarise Hume’s argument, he maintains that while changes in the quantity of money eventually raise or lessen prices, in the time period of moving from one price level to the next, industry, enterprise and social wellbeing is stimulated or depressed. The wise policy is therefore to keep the quantity of money growing slowly, thus promoting a spirit of industry and enterprise in the economy.

Hume on Interest

It is worth saying at the output that Robbins finds Hume’s consideration of interest rather disappointing, compared to his other contributions. This because Hume talks only about factors that will affect interest rates in statical situations, and does not “… discuss the effect of the impact of change, which quite clearly …” needs to be taken into account (P 115).

Suffice to say that in the most general terms, later economists see interest as the price, or rent, one has to pay to use someone else’s money. A modern version of this view is the ‘loanable funds’ theory which adds bank credit to savings and investment, as the factors determining the market rate of interest. (The determination of interest rates will be taken up elsewhere in the blog.)

A brief outline of Hume’s approach is at follows. He starts by attacking the view – sometimes attributed to John Locke, for example – that interest rates are in some straightforward manner related to the quantity of money in the economy.

As above, he proposes a hypothetical situation to argue his point. Thus he says that if the amount of gold or silver in the land were to double or triple overnight, there would be no effect on interest, merely the raising in price of labour and commodities (P 114).

He the propose three factors lad lead to higher interest rates;

- A great demand of borrowing.

- Little riches to supply that demand.

- Great profits arising from commerce.

Clearly this is a supply and demand model of interest, but subject to Robbins comments above.

Hume on Trade

In Hume’s essay ‘On the Balance of Trade’, he begins by saying that those who seek to prohibit the export of commodities, go directly against their own intentions. The more of a commodity that is exported, he maintains, the more will be produced at home – and people at home will be in a position of first offer (P 115).

This is true also, for Hume, as regards the ‘same jealous fear’ concerning the export of money, characterising advocates of the mercantile system. He goes on to demonstrate how the fear that exporting money would cause a negative balance of payments or trade, is unfounded. Note that he is assuming all payments into and out of the country will be made in gold and silver; he takes account of paper money and credit elsewhere.

He begins, as usual, by considering imaginary situation, where four fifths of the gold and silver in Britain were annihilated overnight. In that case he theorises, prices of all goods and services would reduce by that proportion; as a result, Britain’s cheaper exports would flourish, imports would become more expensive and would diminish. There would thus occur an inflow of gold and silver into Britain until the country was, broadly speaking, in the same position relative to the rest of the world as before.

He then considers the inverse situation where Britain’s gold and silver multiplied by five times overnight. Prices of labour and commodities would increase as a result; exports would fall due to the high cost of Britain’s products, but imports would grow as they became so cheap. Gold and silver would then flow out until Britain again attained a level with other countries.

Moreover, he continues, the same processes operate within Britain, where relative prices are maintained between the different provinces.

He concludes by complaining that, notwithstanding the above, the unwise use of paper currency can very effectively divert from a nation all its reserves of precious metals.

To avoid such a result, says Robbins, paper substitutes for gold and silver have to be freely convertible, and banks have to retain appropriate reserves, as do banks of other nations. Given those and other safeguards, Robbins concludes that Hume’s theory on the flow of gold and silver “explains the comparative state of equilibrium prevailing between many countries of the world during the various parts of the nineteenth century” (P 117).

Mandeville, Steuart and Hutcheson

Before turning his attention to Adam Smith, and Political Economy proper, Robbins briefly describes the influences on Smith of three further characters.

Bernard Mandeville 1670 – 1733

Mandeville was an Anglo-Dutch philosopher, political economist and satirist. In 1705 he published a satirical doggerel called the ‘Grumbling Hive’. The argument of the piece was that society was kept in order, the division of labour maintained and employment assured, not by the virtues of people but rather by their ‘vices’.

‘Vices’ in Mandeville’s meaning referred not to vice as we know it today, but to any behaviour in pursuit of the ordinary, normal wants of average men and women; anything, that is, that was not “completely ascetic and austere” (P 119).

In the hive then, after the ordinary pursuit of individual wants, where social ills were ingeniously corrected as they arose, ingenuity was applied to industry to produce conveniences and pleasures so great that the poor lived better than the rich of a few years before.

But then, grumbling and complaining among the bees rose to such a pitch that angry Jove said very well, he would rid the hive of fraud and make things virtuous, in Mandeville’s sense.

As a result, their behaviour became ascetic and austere in dress and food, and in all other ways. At once the economy suffered, then unemployment rose, and everything got worse and worse, producing widespread poverty and misery.

Clearly intended to shock, Mandeville’s view that individual ‘vices’ produced economic wellbeing was widely refuted by 18th century philosophers, including Adam Smith.

But Smith, cunningly, “… was tremendously impressed by Mandeville’s argument [so that there] can be no doubt at all that the effect of Mandeville on Adam Smith’s way of thinking is part of the background to the first chapters of [the Wealth of Nations] (P 121).

James Steuart 1713 – 1780

Steuart was a Scottish baronet, exiled for many years for his support of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. While in exile he studied other nation’s economic systems and, in 1767 published his own economic treatise,’ Principles of Political Economy’, the first book in English with ‘political economy’ in its title.

Robbins calls it ‘careful and well-argued’ and ‘In a way, the best exposition of the wider mercantile system’. That is, Steuart’s book synthesised many of the principles of the mercantile system seen in its wider sense as national economic policy.

It is noted that Smith’s attacks on mercantilism in the Wealth of Nations appear to be made against Steuart’s arguments, although no mention is made of Steuart himself.

Francis Hutcheson 1649 – 1746

Hutcheson was an Irish philosopher who took ideas from John Locke and is known as a founding father of the Scottish Enlightenment. In his role as Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow he taught and influenced, among others, Adam Smith.

In particular he taught Smith that part of moral philosophy that dealt with ethics, and transmitted to him much of the Aristotelian philosophy that had survived the middle ages. He is seen as the bridge between Aristotle and Smith’s analytical economics.

Summary of this Page

This page has looked at economic contributions made in the run up to what has come to be known as ‘Political Economy’, which will be considered on following pages.

Robbins made a distinction between ‘anticipations’ in economic thought and modern economics proper, based on the treatment of the economy as a system.

Systems thinking is described as seeing the economy as a system of relationships, connected through time, where hypotheses can be tried out to explain variations in functioning.

It is traced through the contributions of French writers Richard Cantillon and the later Physiocrats, followed by the Scottish writer David Hume.

Richard Cantillon 1680s – 1734

Robbins begins with a discussion of Richard Cantillon an Irish/French banker and writer on economics. His work was written in the 1730s but not published (posthumously) until 1755.

Robbins compares Cantillon in importance to Adam Smith and other pivotal contributors. His work covered the workings of the economy, monetary and interest theory, and commerce and banking.

Cantillon’s contribution included:-

- Precepts defining land and labour as the sources of wealth

- Descriptions of the components of the economic system and an analysis of the causes of wage differentials, and the hint of a theory on equilibrium processes

- The argument that market prices oscillate around what he calls the ‘intrinsic value’ of items, which he sees as the measure of the quantity of Land and Labour entering into their production

- The delineation of 3 economic classes in society; Landed Aristocracy, Entrepreneurs and Wage earning workers

- The introduction, for the first time, of the term ‘entrepreneur’ into economics

- The development of William Petty’s ‘par’ of Land and Labour, and the calculation of the land equivalents required to support the lifestyles of those in differing social positions

- The mechanism of the processes determining market prices

- The elaboration of the quantity theory of money to stress the importance of the varied circulation paths of money in the influence on price levels

- Contributions on Interest rates, foreign exchange and banking.

Physiocracy

Robbins turns to another important French economic contribution, the distinctive school of thought, whose members became known as the Physiocrats and whom became fashionable with the Royalty of Europe. The leading members of the group were Quesnay and Mirabeau, with Turgot a ‘fellow traveller’.

In 1758 Quesnay published the famous ‘Tableau Economique’ dealing with the circulation of money in society, and which was compared by Mirabeau to the invention of writing and of money.

Robbins indentifies 3 currents underlying Physiocracy; they were heavily pro-agriculture and against the economic support given to manufacture; they had a ‘laissez faire’ view of the economy; they thought that policy should be shaped according to ‘natural law’.

They had a distinctive set of economic ideas:-

They identified 3 groups in society; landowners, rightful recipients of the net product of society, and responsible for all taxation; agricultural workers, whose productive work on the land made the net product, or surplus; manufacturing workers, whose unproductive work produced no surplus, but merely re-worked the surplus from the land.

From this they saw an economic distribution in society based on an annual flow of wealth, as the net product was divided across the three groups, paying for work and goods, enabling workers to obtain subsistence.

Using the Tableau they were able to model situations of economic growth or decline, to theorise about economic equilibrium, and to propose optimal economic policy decisions.

The Physiocrats are seen to be amongst the originators of economics as the study of a system of relationships, something that could be modelled, giving the ability to try out explanatory and quantitative hypotheses. Moreover, they saw the system as working through time, as a process in time; changing the focus of study from wealth to the flow of wealth.

While their view that only agricultural work was productive is seen as misleading, their general distinction between productive and unproductive work has had longer relevance.

Their key contribution was seen by Dobb to be the placing of the ‘net product’ or surplus as the pivot of their system.

Turgot, friend and associate of the Physiocrats, developed their outlook. He felt that the non productivity of manufacturing could not be sustained, and saw that profit – surplus – can result from an essentially capitalist process in agriculture or manufacture.

Some of his other insights were,

To argue against Government intervention in the economy

The recognition of the division of labour

The distinction between ‘market price’, of commodities, determined by supply and demand; and ‘natural price’ that would result in free and competitive conditions

The view that interest is determined by the supply and demand for capital; and that in a competitive free market the returns on all investments will tend towards equality

Finally, he recognised a version of the Law of Diminishing Returns, in that each increase in a productive input would be less and less productive

Important contributions from John Locke and David Hume were then discussed.

John Locke developed, in a 1690 essay, a labour theory of property, where all are entitled to own the fruits of their labour – such as game obtained by hunting, or land cleared for cultivation – on the proviso that such property should not be allowed to go to waste.

Even in advanced societies, he says, that 90% of most commodities result from the labour that has been expended on raw materials.

Locke then, however, using an unconvincing argument says;

As gold and silver does not deteriorate, and cannot go to waste,

It can therefore, without objection, be accumulated by people and used to buy land.

This argument, that people can justly accumulate land and other property produced by the labour of others, was used as an apologia for private property in 18th Century discussion.

The ideas of David Hume on property, money, interest and trade were then outlined.

On property, he argues that property laws do not derive from some sort of natural instinct or natural law.

Property laws, he argues, become necessary in all societies due to their public usefulness; their merit and justification derive from this alone.

He adds that property law can evolve as a result of changes in ideas about public usefulness.

On money, he holds that;

An increase in the quantity of money eventually raises prices

But only after a time period during which the extra money disperses around society

During that dispersion process, industry, enterprise and social wellbeing is stimulated

Therefore it is wise to keep the quantity of money in society growing slowly

A decrease in money supply will of course produce the opposite effect.

On interest, he rejects the view that interest rates are simply related to the quantity of money in the economy. He supports instead a supply and demand model of interest.

On trade, he holds that the prohibition of exports, in order to maintain a positive balance of trade, is counterproductive.

He illustrates by considering an imaginary situation where four fifths of the gold and silver in Britain were annihilated overnight.

In that case, he theorises, prices of all goods and services would similarly reduce

As a result, Britain’s cheaper exports would increase; imports would become more expensive and would diminish

An inflow of gold and silver into Britain would result until the country was, broadly speaking, in the same position relative to the rest of the world as before.

Hume is thus describing an equilibrium process such as that now seen to have prevailed between many countries of the world during the nineteenth century.

Mandeville, Steuart and Hutcheson

Finally, before turning to Adam Smith and Political Economy proper, the influences on Smith of 3 further characters were briefly described.

Mandeville’s view that individuals following their enjoyments produced economic wellbeing was a significant influence on Smith.

Steuart’s writing on mercantile ideas provided Smith with a ready target for his own views.

Hutcheson taught Smith ethics and the relevance of Aristotle to economic thought.

Further discussion of the development of economic theory continues on the page ‘Smith and Ricardo‘, also on the Economic Thought tab. The page discusses classical Political Economy, in the work of these two writers.